There has been a limited amount of fanfare and support – or even discussion for that matter – here in the Empire State on the proposed Geospatial Data Act of 2015. Beyond one or two acknowledgements on the state listservs, the announcement really didn’t generate any buzz or visible discussion throughout the GIS community. Though it comes as no real surprise as few in New York statewide GIS community have had any meaningful exposure or introduction to past legislation/bills regarding federal agencies referenced in the proposed 2015 act introduced by Senator Orrin Hatch of Utah. In absence of any real meaningful dialog here in the New York between the GIS professional community and elected officials on federal legislation (or any geospatial legislation for that matter except perhaps the never-ending “Surveyor” Legislation), one wonders if New York’s federal delegation is even aware of the proposed act. Or its stated benefits.

At the core of the proposed 2015 Act is a combination federal legislation and policies including (in no particular order of importance) OMB Circular A-16, the National Spatial Data Infrastructure (NSDI), and the Federal Geographic Data Committee (FGDC). Very government-like and uber confusing, a little background includes: In 1994, Executive Order 12906 was issued by President Clinton to direct the development of the NSDI. Unfortunately, twenty-one years later, many of the requirements of EO 12906 have never been acted on. Circular A-16 was originally issued in 1953, revised in 1967, revised in 1990 (establishing the FGDC), and revised again in 2002 outlining specific federal agency obligations. A-16 Supplemental Guidance was also issued in 2010. Similar to EO 12906, federal agencies have struggled to implement many of the provisions of OMB A-16 over the same period of time.

The August 2002 revision to Circular No. A-16 was particularly significant in context of naming the stewardship of over 30 data themes to federal agencies in support of both the NSDI and FGDC programs. Specific datasets included:

Biological Resources, Cadastral, Cadastral Offshore, Climate, Cultural and Demographic Statistics, Cultural Resources, Orthophotography, Earth Cover, Elevation Bathymetric, Elevation Terrestrial, Buildings and Facilities, Federal Lands, Flood Hazards, Geodetic Control, Geographic Names, Governmental Units, Geologic, Housing, Hydrology, International Boundaries, Law Enforcements Statistics, Marine Boundaries, Offshore Materials, Outer Continental Shelf Submerged Lands, Public Health, Public Land Conveyance, Shoreline, Soils, Transportation, Vegetation, Watershed boundaries and Wetlands.

While all data themes are clearly important in supporting the broad national NSDI efforts, most New York State local governments have a limited number of day-to-day business work functions directly related to NSDI spatial data themes itemized in the 2002. (In fact many of the 2002 NSDI spatial data themes are only developed and maintained by federal resources.) Adding to the disconnect is that many 2015 local government GIS programs, especially in urban areas, have business needs which are not supported by either the content or spatial accuracy of core 2002 NSDI spatial data themes. For example, local government geospatial programs in the areas of infrastructure management (drinking water, sanitary sewer, and storm water systems), utilities, vehicle routing and tracking, permitting and inspection systems, service delivery programs in the health and human services, local planning, zoning, and economic development activities are not closely aligned with many of the 2002 NSDI spatial data themes. While many federal mapping programs and geospatial datasets continue to be consistent at 1:24,000 (2000 scale), most local urban government GIS programs are built on top of large scale (i.e., 1”=100’ or even 1”=50’) photogrammetric base maps.

Not all is lost, however, as some local data products such as parcel boundaries and planimetrics (building footprints, hydrology, transportation) actually are consistent selected 2002 NSDI spatial data themes (Cadastral, Governmental Units, Hydrology, Geodetic Control, Transportation) albeit at a higher degree of accuracy. Unfortunately, limited capacity or systems have been established to leverage or normalize such datasets into the NSDI.

Unfortunately, even though the federal government continues to identify and list local governments as key stakeholders in most legislative proposals, it’s common belief among federal agencies that resources are not available to monitor or engage local GIS programs (i.e., 3000 counties vs. 50 states). And there continues to be the (wild) belief state level GIS programs can serve as the ‘middle man’ or conduit between local and federal geospatial programs. Somehow magically rolling up local government data for use by federal agencies and integrated into the NSDI. Not really. At least here in New York State. And no, old school NSDI Clearinghouses nor the current rage of soon-to-be-yesterday-news “Open Data” portals being equivalent mechanisms in supporting and maintaining 2002 A-16 data themes.

Perhaps sponsors of the Geospatial Act of 2015 could model collection of local government geospatial data assets after the ongoing efforts associated with the HIFLD (Homeland Infrastructure Foundation Data) program. Though obviously a very different end product from the NSDI, federal agencies producing the HSIP (Homeland Security Infrastructure Protection) Gold and HSIP Freedom datasets have enjoyed relatively decent success in collecting large volumes of local government data – much of which has been paid for at the local level. And many of the same federal agencies associated with the HIFLD program including National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Department of Defense (DOD), and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) have stewardship responsibilities of NSDI spatial data themes. Different. But similar. And adding more bewilderment to the discussion is that it is easier to contribute crowed sourced data (structures) to the USGS than it is for local governments to push large scale photogrammetric data of the same features (structures) to federal agencies and incorporated into the NSDI.

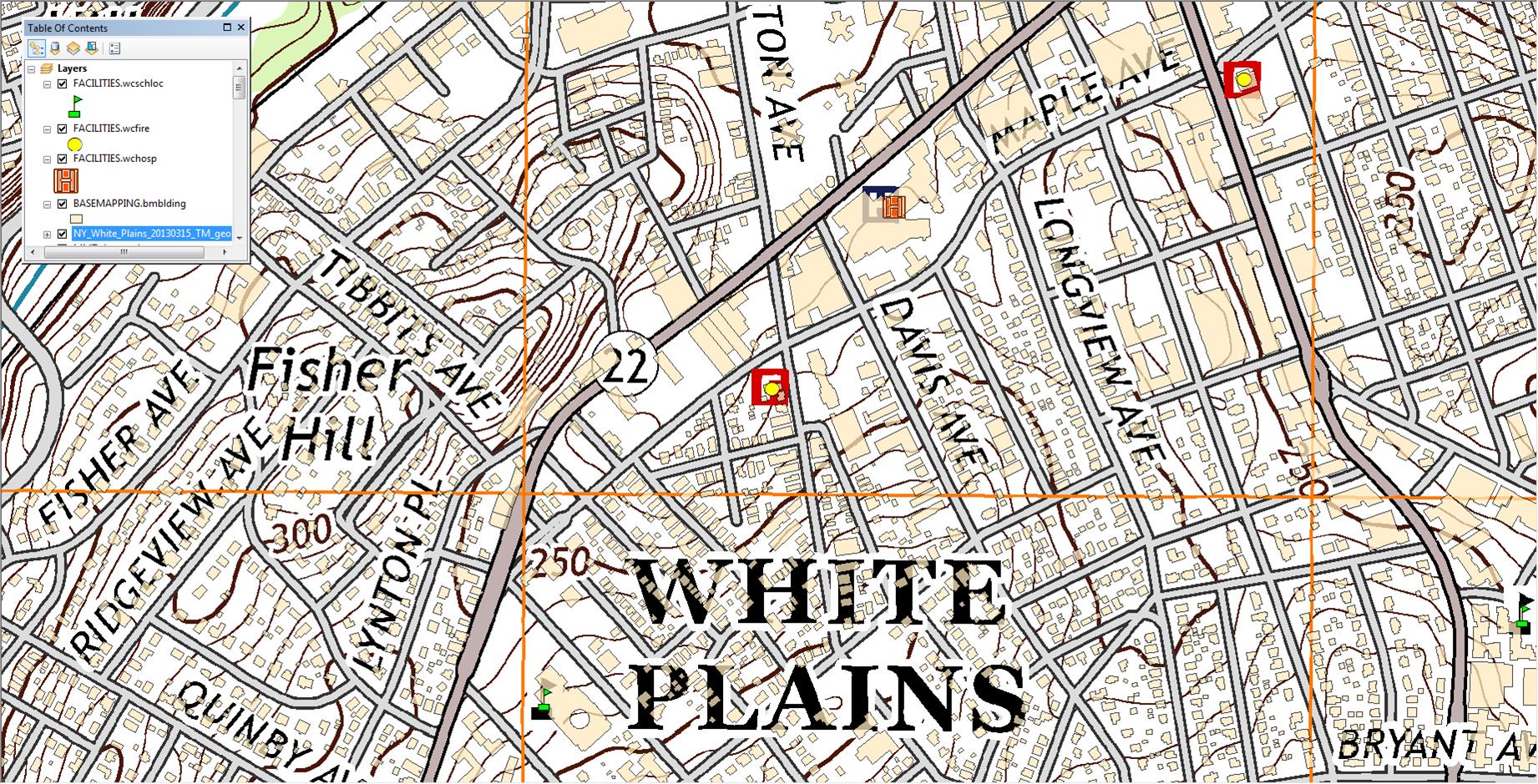

Georeferenced 2013 US Topo White Plains quadrangle. While selected structures such as schools, fire houses and hospitals are identified on the default US Topo product, this image shows also shows how local content such as Westchester County building footprints can be made available to the NSDI structures data theme.

Unless a methodical and accepted process – adopted by pertinent local/state/federal stakeholders – is institutionalized by the FGDC, the Geospatial Data Act of 2015 will continue to be more about federal and state geospatial programs and less about truly integrating and taking advantage of the vast amount of local government data. The Act needs to specify and fund building work flows which communicate directly with the source of the data as well as working towards reducing the reliance on state “middle men” GIS programs as means to acquire local geospatial data. (Local governments were not even mentioned in a February 2015 General Accounting Office report entitled “GEOSPATIAL DATA: Progress Needed on Identifying Expenditures, Building and Utilizing a Data Infrastructure, and Reducing Duplicative Effort”. A report which appears to be eerily similar and a rebaked version of the (ill-fated) 2013 “Map It Once, Use It Many Times” federal geospatial legislation attempting to reposition the federal effort to coordinate National geospatial data development.

Ironically, just one month prior to the Geospatial Data Act of 2015 being introduced, a scathing report was released by the Consortium of Geospatial Organizations (COGO) entitled “Report Card on the U.S. National Spatial Data Infrastructure”. In short an overall “C-“ to NSDI effort over the past two decades. The report falls short in not holding state GIS programs more accountable and responsible as well as most have jockeyed over the past two decades to be seen as enablers and partners of the NSDI effort in context of framework layer stewards, recipients of FGDC grants, and establishing/maintaining NSDI Clearinghouse nodes. States supposedly as “middle men” and conduits to valuable local government geospatial data assets. Perhaps COGO report cards on individual State government GIS programs are forthcoming.

At the end of the day, NSDI supporters actually do have access to a wide range of local government geospatial assets as files, consumable web services, or perhaps through some other middleware provided by a software vendor. Or a combination of all the above. The data and the technology are here. To the end of furthering the intent of the NSDI, legislation like the Geospatial Act of 2015 will fall on deaf ears and not advance as it should unless the federal government establishes the means to directly engage and connect to local governments.