Behind the scenes in the various worlds of films, games, science, military, government, and even the maker culture, is how “geo” has been gradually verging/bringing all of these industries together. The proliferation of smart phones with maps and searches for food and entertainment, geotagging, as well as ride sharing has brought “geo-data” to everyone and seemingly everything. Though geospatial data, geospatial analysis, and basic mapping and cartographic concepts have been well established for many years, it’s only been within recent years that technology has enabled science to push and combine animation and gaming with real world geometry.

Here in the Empire State, faculty at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT), recently ranked #4 in the United States in Video Game Design Schools, Brian Tomaszewski and David Schwartz, are currently working on this technology “convergence” supported through a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF). This effort combines Dr. Tomaszewki’s recognized work focusing on GIS (geographical information systems) applications in the areas of disaster management and risk assessment. He currently serves as Associate Professor and runs the Center for Geographic Information Science and Technology. Augmenting this work is Dr. Schwartz’s background and ongoing work in game programming, prototyping, and design, which he uses to build academic collaborations across RIT program areas including liberal and visual arts, engineering, business, and now the geospatial sciences. He serves as Director and Associate Professor in the School of Interactive Games and Media (IGM).

“The world of games has long sought academic legitimacy, which for the most part has been achieved, by demonstrating ‘seriousness,’” notes Schwartz. Some of the best games are great at teaching players to play those games, many of which have been designed at RIT: Lost and Found (religion), IPAR (computing security), and others.

Lost & Found is a game series that teaches medieval religious legal systems with attention to period accuracy and cultural and historical context. Both games are set in Fustat (Old Cairo) in the 12th Century.

If designers can capture that same immersive engagement for learning, training, education, then game development can make traditional learning, or “non-fun” entertaining and more participatory. There have been several great examples, and there are all kinds of offshoots with government, military, humanitarian, scientific applications, e.g., Instructional Design, Games for Health, and Cybersecurity.

Some of the underlying concepts and building blocks of mashing gaming and GIS software, what is called geogames and location-based games, together include, but not limited to, are:

- Focusing on creating applications around a recent and “real life” historical event that has relevance to end users

- Using industry accepted development tools to create the geogame

- Demonstrate that a location-based game based on real-world data can promote and teach spatial thinking skills

- Provide a “game” to emergency responders and local users that provides a framework for future refinements and enhancements to the game

- Demonstrate that a serious geogames have academic and research merit

With respect to the intersection of gaming and geospatial, Pokemon Go has recently demonstrated people interacting with a virtual world “on top” of the real world, incorporating location-based data into visual interactive, decision-making environment. “The Games for Change” organization based in New York City has generated considerable attention to showing how game creators and social innovators drive real-world change using games that help people to learn, and improve their communities.

Convergence of Films and Games through GIS

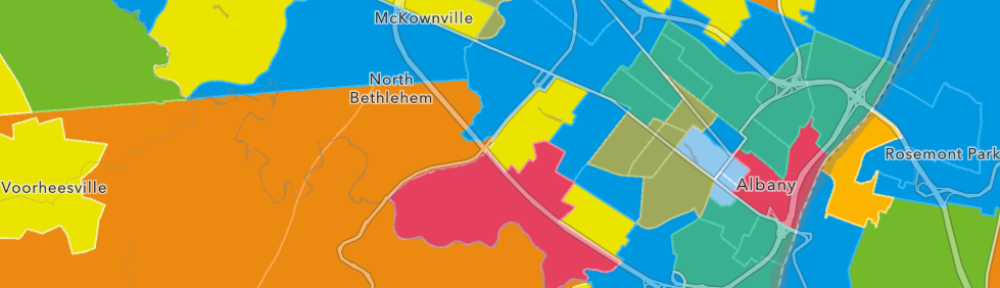

One reason for the excitement on the evolution of geogames is this convergence of various disciplines, technologies, and software environments. Geogames being developed at RIT include free and open source software (FOSS), such as Open Street Map for ubiquitous baseline street data, as well as Unity—a leading and popular game engine for rapidly making games. Unity (which is free for certain applications) has been incredibly important for the “indie” game scene, as well many other industries in professional games, movies, advertising, marketing, and more.

Other key aspects of the convergence include ESRI’s CityEngine, which historically has been used for urban design and 3D modeling. It has had success in various films in making the worlds for Toy Story 2 and Coco. Even RIT’s hometown of Rochester, New York, was an early adopter of City Engine. Other pieces include real-world geospatial datasets, such as elevation models and flooding reach information.

Taking real-world mapping data into City Engine and then porting everything into a game engine enables game developers to visualize a real-world city or landscape. The game then renders graphics and animation, handles interactions (player controls and responses), and embeds (through a lot more programming and design) the game rules (what happens, or outcomes, when the player interacts in specific ways.

Project Lily Pad: Bringing the Pieces Together

Tomaszewski and Schwartz’s NSF grant and support of RIT’s computing college includes research experience for undergraduates (REU), which took eight undergraduate students from around the United States and four School of Interactive Games and Media (IGM) students from RIT to study how geogames can improve visualization for disaster planning. Their study area was city of Dickinson, Texas, where Hurricane Harvey hit the city on August 30, 2017.

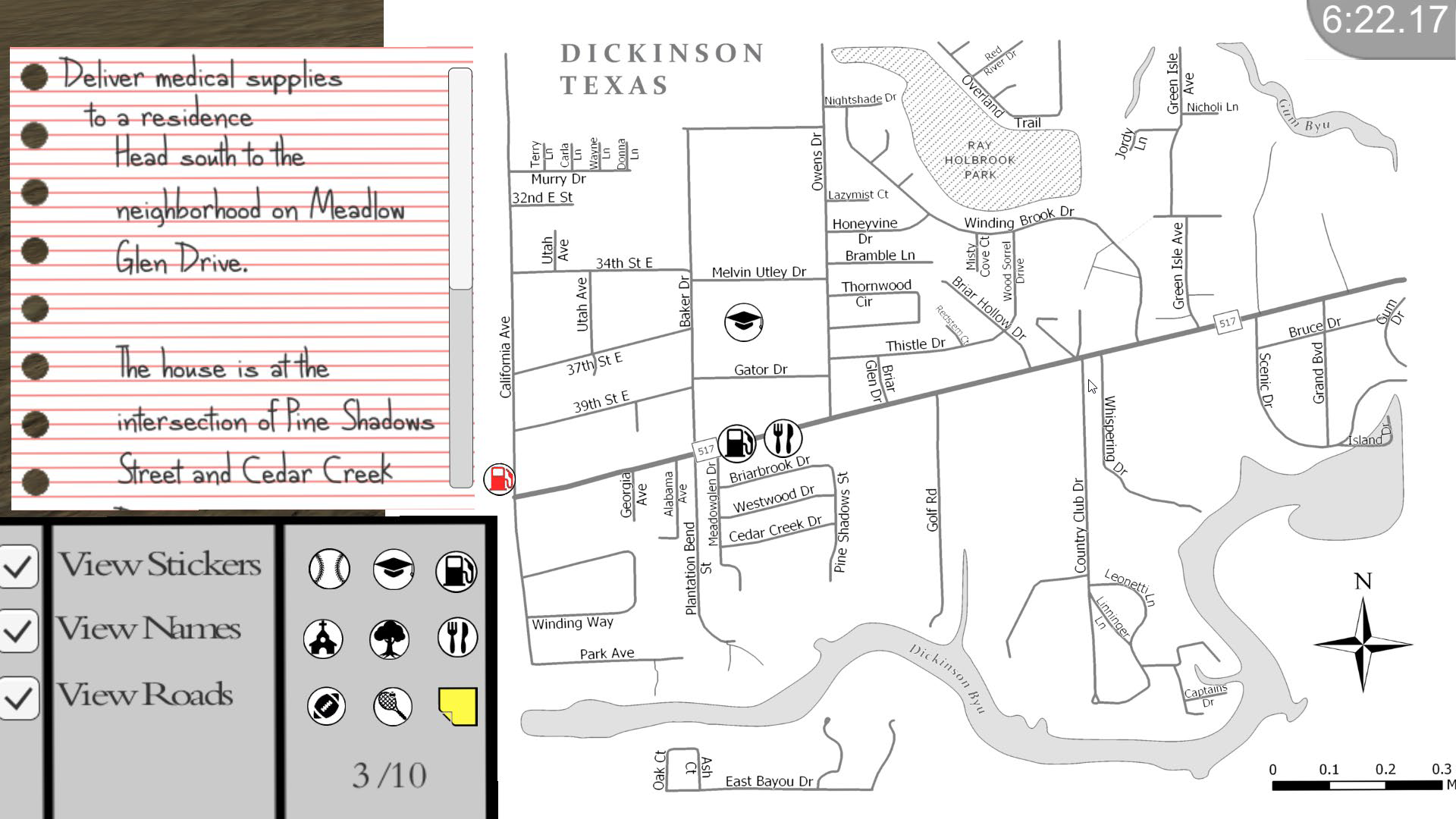

The program was developed integrating GIS and game technology by transferring (and updating) data/models from Open Street Map to ArcGIS to CityEngine and finally to Unity. Both local elevation model and flood data were used to model the city and create the game with almost real-life accuracy as best the team could in only a few weeks of summer work!

Project Lily Pad was developed over Summer 2018 with the purpose of teaching spatial thinking in terms of disaster resilience. The game is set in the city of Dickinson, Texas, which was impacted by Hurricane Harvey on August 20, 2017.

Through a series of lectures and background on geogame research, game jams (rapid prototyping of games), game design, programming, geographical information systems (GIS), spatial thinking, and more, the students developed and implemented Project Lily Pad—a serious geogame to demonstrate how to educate citizens about wayfinding in a disaster, like a flood. The name “Lily Pad” derives from the concept of higher elevations where people go to rise above flooding.

Responders in the Dickinson flooding had a chance to review the first generation of the geogame and offered suggestions. There is a new team of REU and IGM students who will collaborate this summer to improve the game, its workflow, and learn more about what a geogame can do as part of RIT’s new MAGIC building. This project is just one of many that bring together films, games, and other technology. Future ideas include investigating virtual reality (VR) for deeper immersion for players, using procedural generation for creating urban environments, and involving residents for crowd sourcing accuracy of urban environments. It is hoped the geogame concept can be applied for planning for other disaster scenarios besides flooding. The Lily Pad user manual and a game download can be accessed here.

The above images are screenshots from the game. The main character has to navigate Dickinson using a “paper” map and notepad. Playing the game repeated helps the player to develop spatial reasoning of the actual town.

Summary

While the concept has been around for a while (ArcNews Summer 2017), the convergence of geospatial technologies and the game world is only now beginning to take hold in the Empire State. We are fortunate to have work and research being done in this space at a university, which has strong and established geospatial/GIS and game development credentials. The School of Interactive Games and Media has recently hired tenure-track faculty with research interests in geogames, and so, we look forward to more from RIT in their continuing work this summer and into the coming years.

Contact:

David Schwartz, PhD

Rochester Institute of Technology

disvks@rit.edu

Editor’s Note: The author acknowledges the contribution of David Schwartz towards the development and content of this article.