Introduction

A rare treat in eastern upstate New York, mostly in the Adirondacks, although sometimes in the Taconic Highlands along the Massachusetts and Vermont borders and within the Catskills, is to see moose in the wild. Moose (Alces alces) are the largest member of the deer family (Cervidae) and the largest land mammal in New York State. Having been absent from the Empire State since the 1860s, the species began to reenter the state on a continuous basis in the 1980s. While re-establishment of the moose population in New York has been viewed and supported as a positive sign of a healthier, more complete natural ecosystem, it does not come without a range of potential problems associated with their return and the need for proactive management and monitoring by New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) wildlife biologists and researchers.

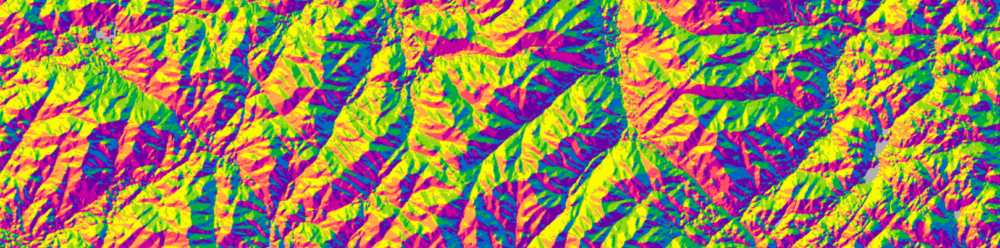

So in 2020 it should come as no surprise that wildlife biologists in New York State – and around the world – are using geospatial technologies to support their work. In addition to estimating moose population size, New York’s wildlife biologists and scientists also focus on improving moose survival and reproductive rates and to assess their diet and health. Assisting the DEC’s work towards researching moose habitat and resource requirements is David W. Kramer, Research Scientist, in the Division of Fish and Wildlife. The toolkit which augments his moose research includes a mixture of GPS, remote sensing imagery, a variety of GIS data layers, and both ESRI and “R” software. R being a free, open source software package for statistical computing and graphics commonly used in the research community.

Population Counts and Observations

To date, Mr. Kramer and colleagues have been observing the locations of 26 moose which were collared with either a Lotek or Telonics GPS unit which can store data “on board” the collar that can then be retrieved by getting the collar back or by getting close enough to the moose to download the data to a receiver. “Uplink” collars can store data on the collar as a backup, but also send daily data uploads via satellite and are then stored online. Moose are captured (to put the collar on) by a crew which “net-gun” the animal from a helicopter. For their research, DEC staff focuses on female moose (cows) for two reasons: (1) wanting to track of how many offspring each cow has; the collars facilitate the “following” of the females in the summer to count calves, and (2) male moose (bulls) go through physiological and body changes during the same period that do not make the collaring of males practical or even unsafe. Data associated with the collars are important in analyzing survival and calving success as well as the geography associated with habitat selection.